By Jack Ward, Eden Hayes, Phoebe Billing & Reese Mautone

The Wirribi Yaluk/Werribee River has been historically recognised as the ‘backbone’ of the Wyndham community but experts say it’s set to deteriorate without expensive interventions.

It snakes its way for about 110 kilometres, from the Wombat State Forest along the Great Dividing Range to the swells of Port Phillip Bay and has been the natural boundary between Woi Wurrung and Boon Wurrung peoples for centuries, with artefacts and burial sites scattered along the waterway.

The river should be a clean natural resource for communities in the west, but residents say they are concerned about its future as population rapidly expands on its banks.

The City of Wyndham has welcomed almost 75,000 new residents to the area since 2016, and is expected to be home to more than 500,000 people by 2040.

The Polman family live in Hoppers Crossing just metres from the riverbank and they adore what Wirribi Yaluk has to offer.

During COVID lockdown Alicia, her husband Bill, and their two young children, Jacobus and Edith, spent hours by the water enjoying the serenity.

“There was one day I remember we were sitting down here, and it was just about time for Edith’s online lesson to start,” she says.

“I quickly sent her teacher an email… and I said I’m really sorry, but she’s not going to make it to her class this morning. I think this is a real hidden treasure around here.”

Eight-year-old Jacobus says the river allows their family to enjoy time together. “I like to go kayaking and sometimes swim in the river. And also, I like rolling down the hill,” he says.

“I take off my shoes, socks and roll up my pants, and then I hop in… and it’s really nice. Sometimes tadpoles come and nibble our feet, and that tickles.”

The Polman family are members of the Werribee River Association (WRA), a community-led effort established in 1981 to protect the waterways of the West.

A team of professionals, supported by hundreds of members and volunteers, work with land and water authorities to help build the biodiversity of the waterway ecosystem.

While Mrs Polman commends efforts to protect the Wirribi Yaluk she says families are still apprehensive about its safety.

“It would be great if it’s something people don’t have to worry about, don’t have to think about, and that’s not often something we can do at a ground level,” she says.

“[We] need to get more people involved, bigger organisations involved; councils and governments.”

The Werribee River is managed by Melbourne Water and considered to be in moderate condition overall.

Calls to improve the river’s quality have been encouraged by the global Swimmable Cities movement. In the lead up to the Paris Olympics, staged along the River Seine, a set of ‘common principles’ were published in the Swimmable Cities Charter empowering decision makers to focus on waterway restoration and quality.

Led by Melbournian Matt Sykes, it’s the first action of the international alliance passionate about urban waterway swimming.

The charter consists of 10 principles they hope will move towards a more sustainable approach when it comes to waterways.

Yarra City Council became the first Australian municipality to sign on to the charter in July of this year, solidifying its commitment to restore the health of Melbourne’s iconic Yarra River.

The Werribee River Association has brought the same vision to Melbourne’s west and signed up to the charter through their partnership with the International Water Keepers Alliance.

Acting CEO of the Association Lisa Fields says the movement is a fantastic initiative in an area of rapid residential growth.

“While there is lots of tree plantings and regeneration works, just the sheer volume of houses and the stormwater runoff is a big impact,” she says. “The water quality is declining in various areas, and it’s mostly due to urbanisation.”

“I’m just pleased that someone is working through this. And if our signature is helpful, that’s great. It just makes a whole lot of sense.”

At the time of writing this article Wyndham City Council was unable to comment about becoming a signatory because the state’s councils were in ‘caretaker mode’. But then-Councillor Robert Szatkowski, who held the Climate Futures and Environmental portfolio, has no issues with signing up to charter.

He sees the river as being the most vital asset to the Wyndham community.

“There’s a lot of talk about the Maribyrnong and the Yarra rivers but comparatively, the Werribee River… has a lot more environmental potential.”

Despite the ‘no swimming’ signs surrounding Bungies Hole in the heart of Werribee’s CBD, Szatkowski says it is swimmable at times.

“The restoration work, the environmental flows that started happening several years ago have definitely helped,” he says.

“It’s a lot healthier now, it’s going really good, but there’s still a lot more work to do.”

One of the issues Council is currently focused on is lack of access to the riverbank.

Szatkowski feels the river is currently “out of sight, out of mind” but says with more attention comes more funding.

“As the public get to see these things and get to see the beauty of this river, you find that there’ll be more public support and then funding.”

The greatest challenge to the Werribee River’s quality is stormwater flowing into the system.

University of Melbourne hydrologist Tim Fletcher has spent his career investigating the challenges of managing stormwater to improve river quality.

“Conceptually, it’s possible, but the reality is more complicated,” he says.

Catchments receive runoff from every inch of the urban landscape, from zinc coating on street signs, cigarettes, to animal faeces and invisible micro rubbers from car tires.

And as the Wyndham community expands, each square metre is a new volume of stormwater that’s going to end up in the stream.

Mr Fletcher believes the easiest time to deal with the problem is exactly when it is being developed. “As you’re building the roads, you’re building a rain garden next to them. As you’re building houses, you’re putting rainwater tanks on those properties.”

There are regulatory requirements that dictate how stormwater should be treated on new housing developments in Victoria but Mr Fletcher says they represent a compromise between what is needed and what is considered feasible or acceptable.

“Now there is a new (Environmental Protection Authority) guidance on stormwater management … It recommends significantly greater targets.”

“That EPA guidance is there, but it’s not yet mandated in the same way [the current] targets are.”

The price of implementing these standards at every new household would cost owners an extra $5,000 to $6,000, according to Mr Fletcher, amounting to more than $1 billion by 2040.

But even more challenging is the daunting task of retrofitting existing dwellings. At a guess, the hydrologist says the cost would be in the $100 millions.

These numbers reflect a best case scenario, where all stakeholders unite with a committed vision.

Melbourne Water agrees stormwater is the most common cause of pollution but says parts of the river may be suitable for swimming during dry weather.

“There are many opportunities to explore and enjoy the Werribee River in ways other than swimming – including along the many riverside trails,” a spokesperson says.

“The swimmable city movement is an opportunity to talk about how everyone can get involved in protecting our waterways through simple solutions such as preventing rubbish, grease, oil and other contaminants from entering our stormwater drainage system.”

If the Wirribi Yaluk was to become a swimmable oasis, it would be a full circle moment for the Wyndham community.

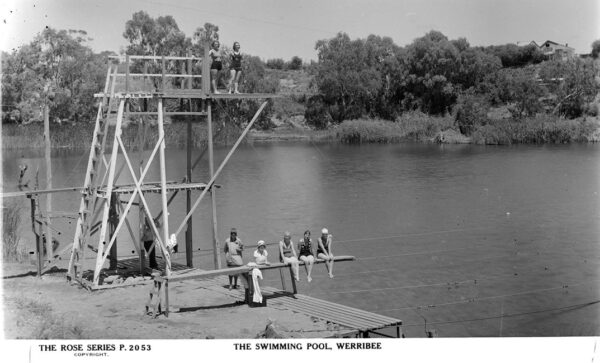

Bungie’s Hole, behind Werribee’s Chirnside Park, used to be a popular swimming spot up until the 1950s and was described in a 1932 Weekly Times article as “one of the best [swimming places] in the state”.

In 1934 an Olympic Pool was built as an alternative after a large number of floods and drownings led to complaints about the river’s safety.

The ‘No Swimming’ sign nailed to a pole on the riverbank is now a clear deterrent to the community.

But Alicia and her fellow Werribee River Association members are defiant in their fight for a clean, swimmable and sustainable river.

“ I would love to see more people down here with us,” she says.