By Jane Toner (guest author while Dominique Hes is on leave)

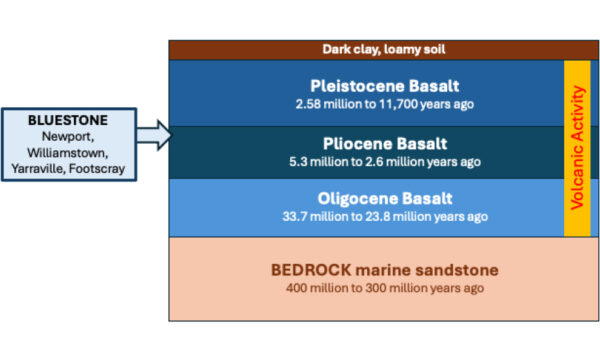

We live on ancient volcanic plains formed by three major volcanic eruptions over the last 35 million years. What can we learn from this place about resilience, adaptability and thriving?

Amidst the hustle and bustle of modern life it’s easy to think of nature as something ‘other’, something over there, something we are separate from.

Remembering our deep connection to nature is an important part of learning from nature. Life has evolved over 3.8 billion years from simple single-celled organisms to richly complex ecosystems. We are one thread within the giant living tapestry that is planet Earth.

We rely on nature for clean air, clean water, nutritious food and more. As well as meeting these basic needs, the experience of connecting with nature supports health and happiness. A 2019 study found that writing down “three good things in nature” each day for a week improved people’s well-being, lasting for a month. Spending time in nature lowers blood pressure and increases your immunity, while boosting mood, reducing stress, and increasing creativity.

With our health and happiness tied to the health of all living beings that share Earth with us, it makes sense for us to care about the nature of the place we live.

All living things follow a deep pattern of tuning in and responding to the place where they live. For example, a tree is anchored where its seed first landed, its growth responds to the soil, sun, wind, rain and interactions with plants and animals in that place. Being attuned to place makes a tree more likely to survive events such as flood and fire. A tree also shapes and gives back to place, providing food, shade and shelter, storing carbon and even a sense of time as it grows and responds to changing seasons.

What can the ecosystems of the western suburbs teach us about creating thriving communities that are attuned and responsive to place?

The Western Volcanic Plains, stretch west from Melbourne almost to the border of South Australia.

A diverse variety of native grassland and woodland ecosystems adapted to shallow soils and low rainfall on the undulating plains between stony outcrops. For tens of thousands of years, these ecosystems flourished in the care of the peoples of the Kulin nation who understood and worked with the land and its cycles.

European colonists saw the cultivated grasslands as perfect for cattle grazing. However, the hard hooves of sheep and cattle were not something the plain’s ecosystems were adapted to, and without the active custodianship of First Nations people, the environment soon degraded with significant reductions in biodiversity. Agriculture and urban development further fragmented ecosystems leading to a high number of unique native species threatened with extinction.

So, what can we learn from ecosystems about adapting to place?

We can learn that reciprocal relationships between people and nature create abundance. We can learn that fire is critical to cycling nutrients back into the land to increase fertility, that clean water and connected landscapes are central to supporting biodiversity.

You can activate this learning in your garden by adding good biochar, planting more endemic species and adding water features. In your life you can learn to slow down, tune in, and be curious about how nature does things. Learn to ask, how does nature meet the challenges of place to create abundance HERE?

References

McEwan, K., et al. (2019). A Smartphone App for Improving Mental Health through Connecting with Urban Nature. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(18).

Victorian Grasslands https://www.viridans.com/ECOVEG/grassland.htm