By Peter Dewar

It’s the prestigious 2024 Cannes Film Festival and Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga is a hit, honoured by a standing ovation. Which is not to mean a garden-variety moment of polite applause. As the film ends, a packed audience rises to their feet, saluting the $350 million, latest Mad Max movie by clapping for a full seven minutes.

The vibe was captured later by actor Chris Hemsworth. In an interview, the action hero said tears welled in Australian director George Miller’s eyes as the 79 year-old, legendary filmmaker leant close to him and murmured ‘Oh … I think they like it.’

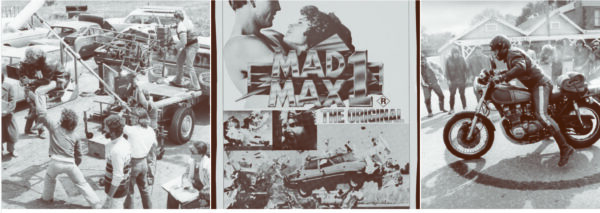

Over five Mad Max films, revenge has been meted out on menacing bikies; two Wasteland communities rescued; and a despot removed thanks to a heroine with one good arm, paving the way for her origin to be revealed. Indeed, much has taken place in the 45 years since two friends began filming a dystopian movie on Geelong (now Princes) Freeway without a permit.

In his book Miller and Max, film critic Luke Buckmaster tells how in 1979 George Miller and another pioneer of modern Australian film, Byron Kennedy, delivered Mad Max from its shambolic, and occasionally life-threatening production in locations west of Melbourne.

George Miller moved from rural Queensland in the early 70s to finalise his medical accreditation in Sydney. In the big smoke, the trainee doctor was able to nourish his creative ambitions. At a workshop in Melbourne, George met another budding filmmaker — twenty-something, inner west lad, Byron Kennedy.

Byron’s mother, Lorna Kennedy, had named her pathologically curious, ‘lion’ of a son after a famous British literary figure. Although high-octane adventure seemed more to Byron’s liking, storytelling was not lost on the young Yarraville boy. As a teen, Byron made good use of an 8-millimetre camera received as a present by making a host of short movies, often with the assistance of his father, Eric Kennedy.

At 21 years-of-age, Byron won the 1969 Kodak trophy with Hobsons Bay, a short film that earned the emerging filmmaker a trip overseas to be mentored by professionals, and propelled Byron into the movie industry.

After buddying up with George Miller, the duo collaborated on short films. Award-winning Violence in the Cinema, Part 1, filmed in Yarraville, was the Australian Government’s official entry in 1973’s Cannes and Moscow film festivals. Byron and George formalised their working relationship with Kennedy Miller Productions and by the mid-70s had come up with an idea for their next and most ambitious project.

With Byron as producer and George as director, they’d make a feature film. Rather than another pretentious Aussie snooze fest, the pair had their heart set on an action-packed one-and-a-half hours. ‘Mum, we’re going to make a movie, but you won’t be getting Gone with the Wind,’ Byron told his mother.

Set in an anarchic, oil-deprived future, the high-rev script was filled with unnerving car chases and fiery scenes in a good guy versus bad guys tale involving characters such as Max Rockatanzky, Toecutter and Bubba.

The violent exposition of road carnage had all the markings of grind-house fodder. To be filmed west of Melbourne, the movie was to be made on an impossible $350,000 budget with a crew of only 15. Just as well Byron’s business nous was matched by his persuasiveness. A group of private investors stumped up the finance. And living under the same roof with the Kennedys, first in Yarraville and later Werribee, Byron and George set out to bring their first feature to the screen.

Morning peak, the freeway connecting Melbourne to Geelong resembles a raceway — and Monday, October 24 1977, the first day of shooting — was no exception. When cast, crew and production trucks turned up on location at an overpass near Laverton looking for the designated parking area, it became clear this was one of the details to have been neglected. There was also the matter of shutting down a freeway. Something not thought through. Or authorised. Amidst screaming and shouting and an assistant director absconding, the solution was left to two crew members with a handful of traffic cones. Radio traffic bulletins soon reported a disturbance on the Geelong Freeway.

In hindsight, mayhem was to be expected. The filmmakers juggled an inadequate budget and a ridiculously tight filming schedule. Add: razzed-up motorbikes, and members of Hells Angels and Vigilantes motorcycle clubs working as stunties. Not to mention, method actors living out a renegade bikers’ lifestyle. It was a recipe for disaster. The filmmakers’ organisational inexperience was evident on day one; within the week, the whole project would be in jeopardy.

A star has no place being driven to location on the back of a powerful 1000cc motor bike. However, three days into filming, the bike ridden by the stunt coordinator and carrying the female lead careered into a semi-trailer on Dynon Road. While not fatal, both were seriously injured.

Director George Miller was now confronted by the loss of two individuals vital to the movie’s success. George rushed into the Kennedy home to call Byron. ‘Mate, we can’t do it. It’s finished. People are going to die,’ warned the uncharacteristically flustered director over the phone. This presented Byron with a major headache: was his friend up to the job of making a feature film? The producer reached out to replace his director with a seasoned hand, and for a few hours Mad Max was in danger of cutting ties with its visionary co-creator.

By morning, a new structure was in place: George returned to the director’s chair while production was strengthened with the addition of senior logistical staff. The stunt coordinator returned to work, albeit in a wheelchair, and the principal female actor was replaced. The schedule rolled on; however, having a cameraman dangle on the back of a motorbike travelling at 180 kmh to obtain low-to-ground images was sure evidence risk-taking was not over. And the consequences made it to the screen.

Late in the movie, bikers collide on a bridge, flailing across the road. Audiences see a rider’s head struck violently by a motorbike sailing through the air, footage too visceral for make believe. In fact, moviegoers are actually witnessing a real accident, and while the stuntie was badly injured, they walked away.

Given this guerrilla style of production, is it really a surprise a decision was made to power a Holden Monaro with a military-grade rocket to film the opening scene?

Byron obtained a Rotanga-Booster rocket from contacts at the Maribyrnong munitions factory. So far so good. However, on set after ‘action’, ignition, and a loud bang, the vehicle detached from its safety rigging. Producer, director and a camera operator watched in horror as a missile dressed up as a car appeared from a pillar of smoke and was hurtling directly towards them.

Fortunately, the massive projectile veered off last minute into a farm paddock in Avalon taking out a fence on the way.

The experience of filming and editing Mad Max left George feeling he was not cut out to make movies. In fact, he hated the film. ‘Don’t worry, George … It’s going to be alright,’ Byron reassured his friend.

The unassuming director needn’t have worried. George’s debut feature resonated, some suggest at a mythical level, with fans around the globe. The Guinness Book of Records later listed Mad Max as the most profitable film ever.

Kennedy Miller Productions subsequently rose as a media force making a host of other productions for television and cinema. Then, in 1983, as the third Mad Max was in pre-production, came a real life plot twist worthy of a Mad Max exploit. Byron died in a helicopter accident. He was 32 years-old.

George dealt with the loss of a close friend, business partner and film collaborator by throwing himself into work, and the Mad Max roller coaster rumbled on under the Kennedy Miller name (later, Kennedy Miller Mitchell).

Byron is remembered by the industry he helped pioneer: each year, the Australian Academy of Cinema and Television Arts (AACTA) presents a Byron Kennedy award to a film-maker displaying outstanding creative enterprise. To our enjoyment, George Miller continues delving deeper into life in a post apocalyptic Wasteland.

Great story Peter, thanks…I had no idea of this film history.

Great film & great article!