By Charlotte Walkling

In 2018, an idea for a network of shared bike paths to improve ‘active transport’ in the west was developed by the community advocacy group Better West under their ‘Spotswood Dreaming’ project. The Hobsons Bay City Council was so impressed by the plan that they adopted and adapted it for their Better Places program and named it The GreenLine.

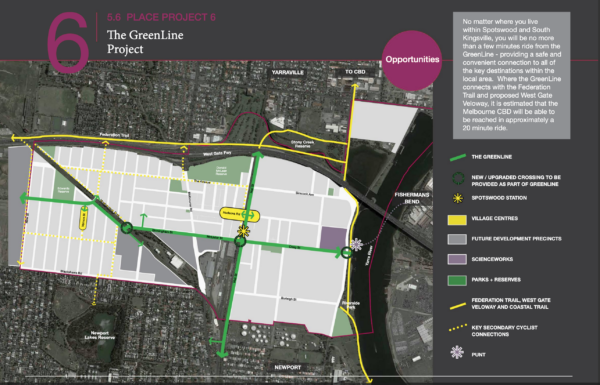

If completed, the GreenLine will be a series of bicycle paths connecting east to west and north to south, along with pedestrian infrastructure. According to Rosa McKenna, President of Better West Inc, and one of the many architects of the GreenLine, the idea is to create “a city that’s actually built for people, not for cars and trucks”.

McKenna says a bike path idea emerged during the Spotswood Dreaming initiative because “the most prominent thing that people talked about was traffic and congestion.”

Spotswood is impacted by major railway lines and major roads as well as Stony Creek and Yarra River. According to McKenna, this means people make more short trips in their cars leading to greater congestion on local roads.

“So, there was a very strong push to have an active transport policy”, says McKenna.

The GreenLine project would create several bike paths running “through the heart of the Spotswood and South Kingsville communities”, according to the Hobsons Bay City Council website.

The council is pitching the GreenLine as the “largest scale and most ambitious project incorporated into the Better Places vision for Spotswood and South Kingsville”.

The north-south GreenLine is due to be completed over the next two financial years, says a Hobsons Bay City Council spokesperson.

“The shared-use path on Hall Street north of Hudsons Road is currently under construction as part of West Gate Tunnel works. Greening and footpath widening on this section of Hall Street will be dependent on the design of the [Spotswood] level crossing removal project.”

However, the spokesperson says that the construction start date for the east-west GreenLine on Birmingham Street and McLister Street is dependent on financing. “Funding is sought from a variety of sources, including Blackspot and TAC grants, and from state and federal governments.”

But Rosa McKenna says the Hobsons Bay City Council is effectively “sabotaging” the project and doubts she’ll ever see it come to fruition. She believes the council is giving up because of too many difficulties.

“I won’t see it in my lifetime”, predicts McKenna. “They appear to be always promoting cars over pedestrians and bikes.”

“They’re taking every opportunity to change the road and create more parking and car space … in what is essentially a bicycle and pedestrian infrastructure. So, we see that we’re being sabotaged continually”, she says.

McKenna says the council hasn’t taken the appropriate route to develop the bike paths or managed to get any developers to contribute. “Nor are they attracting any state government funding to facilitate their plan,” she says.

Urban planner Dr Liam Davies is not surprised that the cost of implementing the GreenLine is prohibitive. Projects like these “very quickly start to cost millions of dollars per kilometre for cycling infrastructure,” says Davies, Associate Director of the Institute for Sensible Transport and lecturer at the Centre for Urban Research at RMIT. He says that’s because they provide much more than just cycling infrastructure.

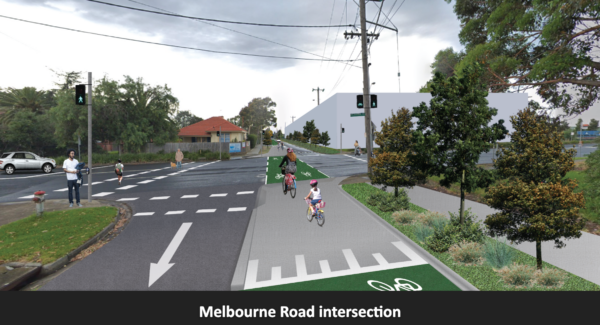

“Urban greening, tree planting … they’re fixing footpaths, and they’re redesigning intersections. And that all adds cost to these projects, which does make them harder for councils to be able to fund,” says Davies.

He says the responsibility to implement such ambitious projects should be on the state government, rather than local councils.

“I think that we need communities to demand ambitious plans. We need councils to set ambitious targets. And we need state governments and Commonwealth governments to get behind these ambitious plans and targets and help make it a reality,” says Davies.

We need “a coordinated state or city-wide approach to how we develop cycling networks that doesn’t leave it up to community groups to propose things to councils and then council’s trying to figure out how to implement them.”

Without a coordinated approach he says, “it becomes a little bit uncoordinated, and I think this is just an example of that”.

It would be wonderful for the state government to provide ongoing grants to local councils for active transport infrastructure, says Davies.

The grants could be provided “on competitive grounds, which means councils have to vie for the right to get this funding. That would mean that this funding would go to the projects that are most worthy … to get the most bang for buck”.

“This would also really steer us towards shifting our transport system,” says Davies. “For the past 70 years we’ve been building our cities around cars”, creating an automotive dependency in our cities.

“We need to be starting to think about how we decarbonize our transport, and that means driving cars less, walking and cycling more, and using public transport more often. And, therefore, for the government to fund walking and cycling projects” by providing “ongoing grants” for active transport infrastructure.

While these are great suggestions for future plans, Rosa McKenna fears the current community vision for a network of bike paths in the inner west is disappearing. She says the council has raised lots of expectations within the community for the project but keeps blocking bike routes for one reason or another.

“So, we’re beginning to call it the Dreamline, not the GreenLine.”

At the time of printing the Victorian Minister for Public and Active Transport had not responded to requests for comment.