By Sian Watkins

Dr John Pardy has, to date, spent most of his life moving west – from Springvale to St Kilda, to Footscray and then to Sunshine in 1999 when Footscray got too expensive to buy a house. A former TAFE teacher with a PhD in vocational education, Pardy was stopped in his tracks when walking past Sunshine Tech one day.

“I know this school. Why is it so familiar to me?” Opening in 1913, Sunshine Tech was one of the first three post-primary government schools built in Melbourne after the 1910 Education Act officially extended public education beyond primary years to create secondary and junior technical schools.

The first state secondary school was Melbourne Continuation School (the forerunner of Melbourne High), which opened in 1905. University High opened in 1910. Collingwood Tech and Melbourne Junior Technical School in West Melbourne opened in 1912, and Sunshine Tech a year later.

As the first government-funded post-primary school in the western suburbs, Sunshine Tech’s existence is tied to the calculated benevolence of industrialist H. V. McKay, who donated the land and £2000 to the Education Department to build the school.

Of the 70 students who enrolled at Sunshine Tech in its first year, 44 were apprentices at McKay’s Sunshine Harvester factory close by. The apprentices attended the senior classes half a day a week in a work/training model pioneered by McKay and adopted across the state in 1928 under the Victorian Apprenticeship Commission.

Female students were accommodated at Sunshine Tech in 1915 (shorthand, typing and bookkeeping) and Sunshine Girls Technical College was officially established on the site in 1921. It was the first dedicated girls’ technical college in Victoria.

Secondary technical schools became unfashionable in the 1980s but Sunshine Tech survived until 1991, making it the longest running secondary technical school in Victoria.

The Sunshine Tech buildings that stopped Pardy in his tracks were the boys’ and girls’ blocks, the Nash and Henty wings, designed by chief public works architect Percy Everett and which were completed in 1940 and 1947.

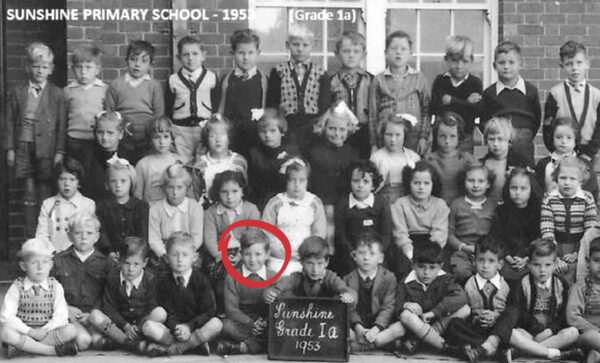

Courtesy of Public Records Office of Victoria

They have commanded much of his time since he was alerted in 2021 to a ‘notice of intent to demolish’ on the site. He speedily wrote a study of the school’s history to support a nomination by Brimbank Council for the buildings to be included on the Victorian Heritage Register.

The State Government has since indicated that it will not demolish the buildings, but Brimbank’s heritage nomination to protect the site was rejected by Heritage Victoria earlier this year. Inclusion on the register affords legal protection and stops an owner from demolishing the buildings.

Among its reasons for rejecting the application was that the school’s original buildings had been demolished; that other technical schools had been built with the support of an influential benefactor, and that the early provision of vocational education for girls and women was already embodied in the slightly older Emily McPherson College.

Pardy, president of the Sunshine and District Historical Society for the past 13 years, will be an expert witness for Brimbank Council when it appeals against Heritage Victoria’s decision in late October.

Pardy says the Henty and Nash buildings “are significant … in relation to secondary schooling, class, labour, technical education and the way Melbourne developed culturally and industrially”.

He says many fascinating industrial buildings in Sunshine have been demolished without any regard or thought for their significance.

“The West is often taken for granted. Look at the recent listing of the Curtin Hotel [in Carlton] which was saved in a minute. Working class people and their histories and the institutions and buildings in their neighbourhoods are routinely overlooked and ignored. They seem to get done over all the time.”

Pardy was always interested in history, “particularly the history of work … how it changes and how people come to do different jobs in different times”.

Not long after moving to Sunshine, John met Frank and Olwen Ford, who founded the Sunshine and District Historical Society in 1972. Frank, who died in 2016, was an influential mentor to John when they spent time at the Society’s cottage in Deer Park where its archives are housed. They shared an interest in the history of education in Victoria. Frank had lectured at Toorak Teachers College before his retirement. John was a lecturer in the Faculty of Education at Monash. Frank “taught me how to think historically”, says John, “to understand how things emerged and to think about why they emerged in particular times”.

Today, the society runs open days at the heritage-listed Black Powder Mill on the former Albion Explosive Factory site in Cairnlea, as well as many other local history activities throughout the year.

There is much interesting stuff on the society’s website, such as the long list of notable people who grew up, lived or worked in Sunshine – people such as cricketer Keith Miller, golfer Craig Parry, author A. B. Facey (Maidstone), fashion designer Richard Tyler and his mother, Topsie Tyler, a renowned seamstress, and freestyle skier Lydia Lassila. One entry stands out as evidence enough for putting ‘Sunny Tech’ on the heritage register: AC/DC played in the school’s hall in 1975. Bon Scott, its lead singer, lived in Couch Street, Sunshine, until he was about 10.

The society (sunshinehistoricalsociety.org.au) has a home at the Hunt Club in Deer Park, which is open on Tuesdays between 10am and 2pm (telephone 9249 4614). Its curator, John Alchin, and other volunteer members are at the Brimbank Library between 2pm and 4pm on Wednesdays. To contact the society, email secretary@sunshinehistoricalsociety.org.au

Brought to you by Dr. Daniel Mulino, Federal Member for Fraser

If you would like to nominate a Champion of the West, email daniel.mulino.mp@aph.gov.au