By Abdulrahman Abdulkader, Vic Bailey, and Yvette Campitelli-Slee (RMIT Journalism graduating students)

Bia Cândido paints canvases with swirls and strokes of saturated blues, yellows, pinks, and greens. Vibrant vegetation and flowers serve as the backdrop for colourful depictions of her family’s Brazilian culture.

The 19-year-old graphic design student from Wyndham infuses her work with deep meaning, speaking to the care and time she invests in doing what she loves.

“I cannot really focus on anything. But with art, I will spend three hours just painting. It’s very much like therapy,” Bia says.

“It’s like something I was born to do.”

But when it came to enrolling in the degree she would pursue at university, a Fine Arts course wasn’t up for consideration.

It wasn’t due to a lack of interest or a different dream taking priority. Rather, it was because of the cost and risk associated with carrying a heavy financial burden.

According to the Victorian Council of Social Service , suburbs in Wyndham, including Werribee, Wyndham Vale, and Tarneit, experience some of the state’s highest levels of economic disadvantage.

“If I was going to spend all this money going to uni for, let’s say, a Fine Arts degree, and I can’t even see myself getting a job afterwards or making that money back somehow, what is the point?” Bia says.

While Bia’s story is a personal one, it’s reflective of a broader trend emerging at Australian universities – a trend experts warn could further entrench educational inequity.

Surging tuition fees, mounting debt, and stigma are pricing low-income students out of Arts degrees (humanities, fine arts etc) and our creative industries.

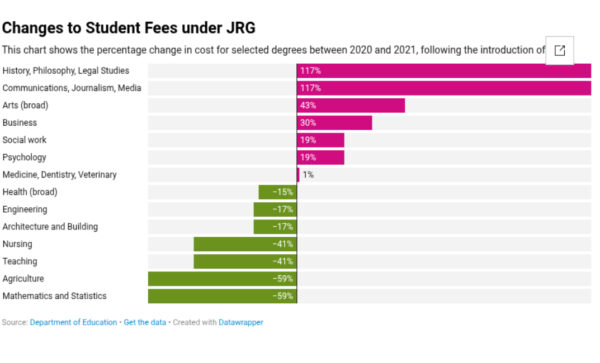

One of the most significant factors behind this shift was the change to degree fees under the Job-Ready Graduates (JRG) package .

Introduced in 2020 by Scott Morrison’s federal Coalition government, JRG lowered the tuition cost for supposed ‘high demand’ degrees and raised the price for ‘low demand’ ones.

The cost for a history or media degree rose by 117 per cent under JRG. A degree in mathematics dropped by 59 per cent.

According to the JRG policy itself, “the reforms were the first major change to higher education funding rates since 2005 when the Commonwealth Grant Scheme was introduced.”

Funded by the Department of Education, the Australian Centre for Student Equity and Success (ACSES) collates research and offers reform recommendations for student equity in higher education.

Associate Professor Tim Pitman is the ACSES Trials and Evaluation Director. He says before 2020 there were “three logics” for pricing education in Australia: “social justice”, “cost recovery”, and “return on investment”.

But the implementation of JRG “completely ended that”.

“It suddenly said, we’re pricing a course not based on how much it costs to teach or how much the student will earn in the future, but to shift students away from what the government thought were ‘wrong’ degrees and into ‘right’ degrees,” Pitman says.

ACSES notes it cannot yet determine the full impact of JRG on course completion rates, but early data suggests the reforms have not achieved their goal and may only be burdening students with additional debt.

“There’s no direct evidence that JRG is having its effect. So, you’re penalising these students, and doubly penalising students from disadvantaged backgrounds because they have less disposable income,” Pitman says.

Last year, Federal Education Minister Jason Clare released the Australian Universities Accord Final Report – which explores higher education challenges and offers a plan to improve the sector.

Previously unpublished figures from the Department of Education graphed the proportion of commencing students from a low-socioeconomic background between 1989 and 2022.

The overall proportion increased from 13.5 per cent in 1989 to 17.4 per cent in 2022, but following the announcement of JRG and Covid-19 lockdowns in 2020, it fell sharply from a record high.

Data from Universities Australia reveals enrolments in ‘Society and Culture’ degrees reduced by over 26,000 between 2021 and 2023.

For those in ‘Creative Arts’ degrees, enrolments dropped by more than 5,000 in the same period.

“A lot of universities and art schools are losing their arts programs. They’re having them merged or absorbed by other disciplines.”

“Federation University in Ballarat is under a lot of pressure now to reduce their arts program. UNSW in Sydney also just lost funding for some of their arts schools.”

“When there are fewer places [offering arts], the competition increases for those places. And when the competition increases, people with more resources, people that can afford to send their kids to private schools or just pay for a degree, they’re going to get in,” Pitman says.

“It definitely is harder for people from certain communities, like if you don’t come from a wealthy family, to pursue arts. To tell your parents that you want to do a design degree is a lot harder, especially immigrant parents. They’ll be like, ‘Girl, what? Go be a nurse’,” says Bia Cândido.

But Amelia Bird, the Executive Officer of not-for-profit organisation Art Education Victoria, says these discrepancies also stem from a lack of available programs.

“We’re really having trouble with the lack of funding and the funding cuts,” Bird says.

Art Education Victoria represents teachers, and advocates for quality visual arts education through improved resourcing.

“It’s so vital for [low-socioeconomic status students] to feel their expression through the arts is valued, and that we’re there to support them to integrate that into a career if they want,” Bird says.

The financial pressure of significant higher education debt can also price students out of our creative fields.

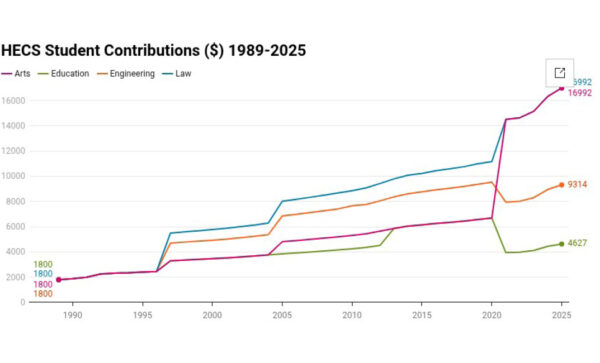

Under Australia’s Higher Education Contribution Scheme (HECS), the federal government subsidises part of a Commonwealth supported student’s tuition fee. The remaining portion, called the Student Contribution Amount, can be paid up front or deferred through a HECS loan.

In recent years, the Student Contribution Amount for arts and humanities degrees has surged, meaning more individual debt. Before 1989, university was free.

Dr Ryan says the package told students wanting to pursue their passion with higher education that policy makers didn’t “respect the study of those areas”.

“Calling these courses ‘low-demand’ makes it seem like they’re less important,” Bia says.

“It is so discouraging, and I think the government should realise that.”

Creative Industries reports people with higher household incomes have higher rates of arts participation. Those who identify as ‘working-class’ say they are less likely to participate in the arts “because it’s too expensive”.

“The reason I feel like I can’t get a job afterwards is because other people would tell me that, often people that aren’t in creative fields,” Bia says.

“But when you’re in a design course and you talk to your teachers, who had all these fun projects and have found their niche, you see that people do want and need art.”

Bird agrees and emphasises how this learning “goes beyond the classroom”, teaching “critical thinking” and “cultural literacy”.

“[JRG] didn’t actually deter students or push them into those other fields. It may have stopped students from applying but I think the students that are passionate about those areas are going to be passionate for life,” Bird says.

Earlier this year, more than 100 high profile Australian creatives signed an Open Letter to the Prime Minister urging the government to abolish JRG.

While Labor was critical of the initial bill, no policy to scrap JRG has entered parliament.

“The one change that I would make if I were Education Minister tomorrow is to decrease the burden associated with undertaking tertiary education studies in this country because it is out of control,” Dr Ryan says.

Bia Cândido says celebrating the creativity of young Australians will support them to pursue their passion through education.

“It is such a lie that you can’t get a job [in the arts]. You can. Especially if you find your niche and fill a gap,” she says.

“And imagine if that was encouraged? Kids could be doing so many cool things.”

For Bia, and thousands like her, the dream hasn’t disappeared – it’s just waiting for a country willing to invest in it.