By Raia Flinos, Sylvia Erson and Sarah Toomey (RMIT Journalism graduating students)

In the heart of the western suburbs lies a remnant of the vast grasslands that once stretched across nearly a third of the state. Now confined by a barbed wire fence, with litter scattered around the borders, this patch contains unique plants and animals with a deep human history.

A nearby environment similar to this one has revealed a hidden secret: the Victorian grassland earless dragon. Thought to be extinct for more than 50 years, it was rediscovered in 2023. This little dragon measures just 15cm from head to tail and was once abundant in the grasslands. Habitat loss and degradation, as well as the introduction of predators such as foxes and feral cats, has led to a catastrophic decline in their numbers.

Until its rediscovery, the Victorian grassland earless dragon was another casualty on the long list of victims of environmental colonialism—a process of systematically altering the landscape in the European style.

“Plants and animals are a part of settler colonialism, not just people and the dispossession of Indigenous peoples. There are all these other factors. Colonisation wasn’t an event; it is a structure,” says Jack Norris, historian, lecturer, author and western suburbs local.

In the early days of colonisation, settlers asserted ownership and transformed the landscape, which was a powerful tool in acclimatising to their new environment.

“The idea of settler colonialism is based on supplanting what was here,” Norris said.

“Initially, when the British invaded and colonised Victoria, they were interested mostly in exploiting the landscape.”

Ancient native grasslands were cleared for European agricultural practices, which was the beginning of the decline of local plants and animals. Foreign trees, such as the London plane, which are still common around the state, were planted in their hundreds.

The vast majority of Australian ecosystems have been disrupted through the process of environmental colonialism, and unique environments like the grasslands are still under huge duress.

Australia’s ecosystems are complex, so changes such as the introduction of foreign plants have countless flow-on effects.

“In an ecosystem, there’s so many connections, and connections, which, to this day, we don’t understand,” says Ben Cullen, a conservation ecologist at Trust for Nature, a not-for-profit organisation.

“Where a bit of fungi is related to an orchid that’s related to a pollinator that’s related to a bird. And when you break that chain, it changes the ecosystem,” he says.

“We’ve got ecological disasters, collapse, ecocide if you will. The Australian landscape is not healthy. And it’s going to take centuries to mend.”

Not only do the grasslands offer vast ecological value, but they are of indescribable cultural value to Indigenous groups who lived on and cared for the land for millennia.

“It’s where the orchids grow, where the yam daisy grows, where the lily grows, that’s where the kangaroos are, where the echidna is. The grasslands were incredibly important. In fact, those people, the Bunurong, the Wadawurrung, they all saw themselves as being grass people,” says author Bruce Pascoe, a Yuin, Bunurong and Tasmanian man.

As a result of colonisation, Traditional Owners are no longer the primary carers for the land, but they share their deep cultural knowledge with community, friendship groups, and councils.

“It’s three per cent of the population trying to educate the other 97 per cent,” says Pascoe..

Today, these groups help to conserve what is left of the grasslands through planting, habitat restoration, and community education.

The councils they work with determine funding, policy, and future use of public land. The councils benefit from the local knowledge and hands-on efforts the groups provide, while community groups gain funding and support needed to continue their work.

Boundless plains

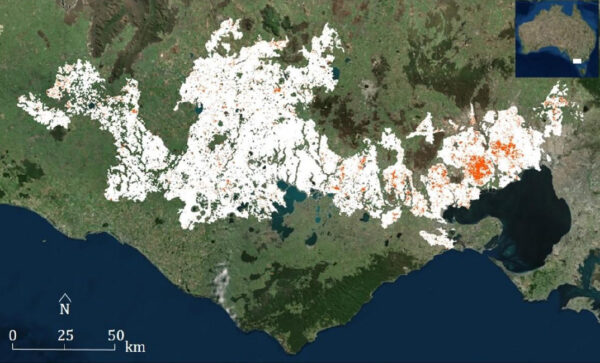

The grasslands within the Greater Melbourne area sit on vast volcanic plains; Wurundjeri and Bunurong land.

These plains have some of the most fertile soil and consistent rainfall in Victoria. This combination is the perfect recipe for some of the state’s richest and most diverse wildlife with the grasslands home to plants and animals found nowhere else in the world.

Before colonisation, the grasslands were full of native orchids, daisies, lilies, peas and grasses, which provided habitat to small animals, including the striped legless lizard, Victorian grassland earless dragon, fat-tailed dunnart, golden sun moths, growling grass frogs and many more.

“It’s a very old landscape. Just like the steppes of North Asia and the prairies of America, Victoria’s got the Victorian volcanic plains,” says Jordan Crooks of the Victorian National Parks Association.

Indigenous people used fire to maintain the grasslands by burning off some plants, stimulating the growth of others and attracting animals for hunting. The grasslands offered an abundance of food and tubers were central to this. The Murnong, or Yam Daisy, was a staple food for the Wurundjeri People, once plentiful in the grasslands but now critically endangered due to sheep grazing.

Settlers saw the grasslands as ideal for agriculture; they offered grazing for imported domestic animals and, due to their lightly wooded nature, were easy to convert to crops for European farming practices.

“Europeans had no idea how to care for this country, so they brought hard hoofed animals over, they ignored the Aboriginal grains and tubers and planted wheat and potatoes in their stead, all of them annuals, which were suited to the Northern Hemisphere, not necessarily to the Southern Hemisphere,” says Bruce Pascoe.

When colonisation occurred, the British Crown assumed ownership of the land. It then gave or sold it to individual settlers. These processes saw the removal of Indigenous peoples from their country, often by force.

“We were locked off the land… you can’t care for it if you’re not allowed to stand on it,” says Pascoe.

European farming practices led to severe degradation of the soil. Knowledge of the country and Indigenous farming practices was disrupted, and knowledge of caring for the land, native plants, and animals was ignored.

These days the biggest threats to remaining grasslands are “urban development […] which threatens a lot of high-quality native grasslands and wildlife habitat,” says Jordan Crooks. “And then further out, unsustainable farming practices and also land clearing.”

However, it’s not all doom and gloom. Like the Victorian earless dragon, other species previously thought to be extinct have been rediscovered, including the Sunshine Diuris (Diuris fragrantissima).

While there are fewer than 30 plants of the Sunshine Diuris left in the wild, they are now managed by a recovery team that works to maintain and advance wild populations, as well as reintroduce cultivated plants into new locations.

The earless dragon has been identified as the most at-risk lizard or snake species in Australia. The dragon is now part of a breeding program at Zoos Victoria.

Alongside these efforts, private land owners, community groups, and councils are working to restore native ecosystems and counteract the ongoing effects of introduced plants and animals.

Grassroots

Alongside these efforts, private land owners, community groups, and councils are working to restore native ecosystems and counteract the ongoing effects of introduced plants and animals.

Volunteer community friendship groups like Friends of Kororoit Creek are leading these efforts.

They have spent decades planting vegetation, removing invasive species, and helping protect their local environment. They consult with Traditional Owners and encourage locals to help heal and restore the land.

“We only plant indigenous plants local to the area, and they have to have the right provenance,” says Jessica Gerger, president of Friends of Kororoit Creek.

The group hosts regular planting days, clean-up events, and educational sessions.

At their home base, the Bug Rug in Sunshine West, they collaborated with Indigenous artist Fiona Clark and her husband, Kenneth McKean, to create Walan-walan, a circular meeting place featuring sculptures based on animal totems from the Wurundjeri Woi Wurrung seasonal calendar.

They use this space to engage the community with Indigenous cultural practices; hosting smoking ceremonies, educational workshops, and storytelling sessions.

“We encourage people to say thank you to the land whenever they’re on it,” Gerger says. “It feels like the very bare minimum for living on this stolen land is to restore it and protect it.”

Gerger says restoration isn’t just about planting; it’s about preserving what remains. She urges people to find friendship groups in their area and volunteer.

“Get involved in your local group and help improve the land that you live on.”

Friends of Kororoit Creek was formed in 2001, thanks to a grant from Brimbank City Council, and was at first led by council staff. Now, they are their own registered charity with a committee, but they do receive yearly conservation support from the council and continue to have a strong working relationship.

Policy to planting

Brimbank City Council, which oversees much of the western suburbs, recognises the vital role of these groups. Mayor Thuy Dang says the council’s goal of 30% canopy cover in their Local Government Area by 2046 requires community cooperation.

“To achieve this target, we need all landowners, including residents, private developers, and State Agencies, to be retaining and planting trees,” Dang says.

She highlights the critical role trees play in enhancing biodiversity, providing shade, and improving air quality. Brimbank aims to plant mainly native species, but species selection is site-specific, taking into account the environmental needs of each location.

Brimbank Council has an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander committee, which consults on Indigenous matters, but Council has not confirmed whether the committee consults on tree-planting and other environmental decisions.

Maribyrnong City Council works actively with the Bunurong Land Council to integrate Indigenous perspectives into its environmental practices. Mayor Pradeep Tiwari says while they do use both invasive and native species when planting, they prioritise native trees in natural areas and in locations with ample ground space for roots.

“Exotic tree species are commonly selected for highly modified urban environments. This is due to their tolerance for pruning around services, ability to perform in limited spaces both above and below ground, and provide quality shade over hard surfaces in summer,” Tiwari says.

Recently, Maribyrnong worked with the Bunurong Land Council to convert the Lae Street Nursery into a public space, a demonstration of how Indigenous knowledge and perspectives can help guide land management and blend cultural and ecological restoration.

The state of Victoria’s grassland and urban environments reflect the ongoing effects of colonisation right across the country due to exploitation since British arrival. Ordinary citizens, councils, state and federal governments, in collaboration with Traditional Owners, are hopeful that unique environments can be conserved and restored.

Additional reporting from Barbara Heggen.